Challenging Stereotypes:

A Decade-Long Journey in Computer Science as a Vietnamese Woman

Ten years ago, back in 2014 — I was a high school senior preparing for the Vietnamese National High School Graduation Examination (Kỳ thi Trung học Phổ thông Quốc gia). This standardized test is a major milestone for all Vietnamese high school students, serving two primary purposes:

- High School Graduation

- Admission to undergraduate programs at universities or junior colleges

Like many of my peers at the time, I found myself consumed by existential questions about my future, constantly wrestling with doubts and uncertainties.

I wanted to apply for the Mathematics-Informatics program at Hanoi University of Science and Technology (top #1 university in Vietnam for Science Technology Engineer Mathematics (STEM)).

But I hesitated.

The 17-year-old me was riddled with self-doubt:

“Am I a good fit for the field of STEM?”

“Should girls even consider studying Computer Science?”

Image: Illustration of me, 10 years ago, reflecting on my potential in Computer Science.

Back then, I was awash with questions, uncertainties swirling around me, and no clear path forward. Yet through a complex tapestry of choices and unexpected turns, here I am a decade later, established in this very field.

Now, ten years later, if I could travel back to 2014 and meet my younger self, wrestling with those deep-seated doubts, what wisdom would I share?

This post is dedicated to young girls, especially Vietnamese junior students, yearning for a glimmer of hope or a spark of inspiration to pursue Computer Science. My story—intensely personal and far from a comprehensive guide— but hopefully can to offer a glimpse into what it truly means to be a Vietnamese woman navigating this dynamic landscape.

“Yes, you belong to Computer Science.”

“Your 10-year-later self will be proud of you today!”

Image: If I could travel back in time, what would I tell my younger self?

Table of content

About Me:「 ✦ Thao Nguyen ✦ 」

About Me:「 ✦ Thao Nguyen ✦ 」

Hello there, I'm Thao (Thao Nguyen). I'm a PhD student in Computer Science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA.

I graduated from Thai Nguyen High School for the Gifted, majoring in Mathematics (Class K24). Later, I pursued a degree in Mathematics and Computer Science (Talent Engineering Program) at Hanoi University of Science and Technology.

In my final year of university (2019), I was fortunate to be among the first 10 AI Residents at VinAI Research (Batch 1). My experiences at VinAI were instrumental in opening doors to research and eventually led me to apply for a PhD program in the United States.

As I write this (December 2024), I am in my third year of the Ph.D. program, working with Professor Yong Jae Lee. Beyond Computer Science, I am also pursuing a PhD Minor in Educational Psychology.

The Doubts I Used to Have… And is it normal to have these doubts?

Ten years ago, I’ve had plenty of questions and uncertainties about whether should I pursuit Computer Science/ STEM. But what stands out most—what I remember most vividly—are three key questions:

(1) Is Computer Science a field meant only for men?

(2) Is Computer Science only for those with outstanding intelligence?

(3) Are women in Computer Science often unattractive and less likely to find love or get married?

Before diving into each question, I want to say that having questions like these, and feeling uneasy about them, is entirely normal.

Questions like “Can I do well in this field?” or “Do I have the traits or qualities necessary for people in this field?” are perfectly reasonable and natural. In Educational Psychology, this process is called prototype matching, or, in simpler terms, “comparing yourself to role models.” When making a decision to pursue something, people often tend to compare themselves to “role models” who might have made similar choices. Their decision is influenced by how closely they perceive themselves to align with these models. For example, when you’re searching for housing near your university, you might explore where other students from your school usually rent. This shapes your decision.

Prototype matching is a strategy whereby decisions—from the mundane to the profound—are influenced by overlap in one's self-concept with impressions of a prototypical other. When making a complex social decision such as where to live next school year or whether to begin smoking as an adolescent, people compare themselves with a prototype of the typical person who would choose each possible option, and choose the outcome that produces the least discrepancy between the self and the prototype.

This process of self-to-prototype matching has been shown in research to affect whether a student chooses to pursue a particular major. For instance, if you feel you resemble the “role models” you associate with science and technology, you’re more likely to feel confident about choosing that field. Conversely, if you feel you don’t match those role models, you might hesitate or question your ability to succeed in it.

STEM is one of those fields that I think comes with many “role models” or stereotypes (e.g., “usually male,” “intelligent,” “socially awkward,” etc.). I’ve been through these processes myself and found that these “role models” and the act of “comparing yourself to them” can sometimes discourage you from choosing a path in science and engineering. Research has shown that female students, when they feel they don’t match the “science researcher” archetype, are less likely to register for science and technology-related courses.

Ten years later, now that I understand how “role models” can influence the decision to study a field. Let me revisit the common “role models” people often associate with Computer Science; and how my perceptions has changed!

Computer Science is for Men

Computer Scientist is a men

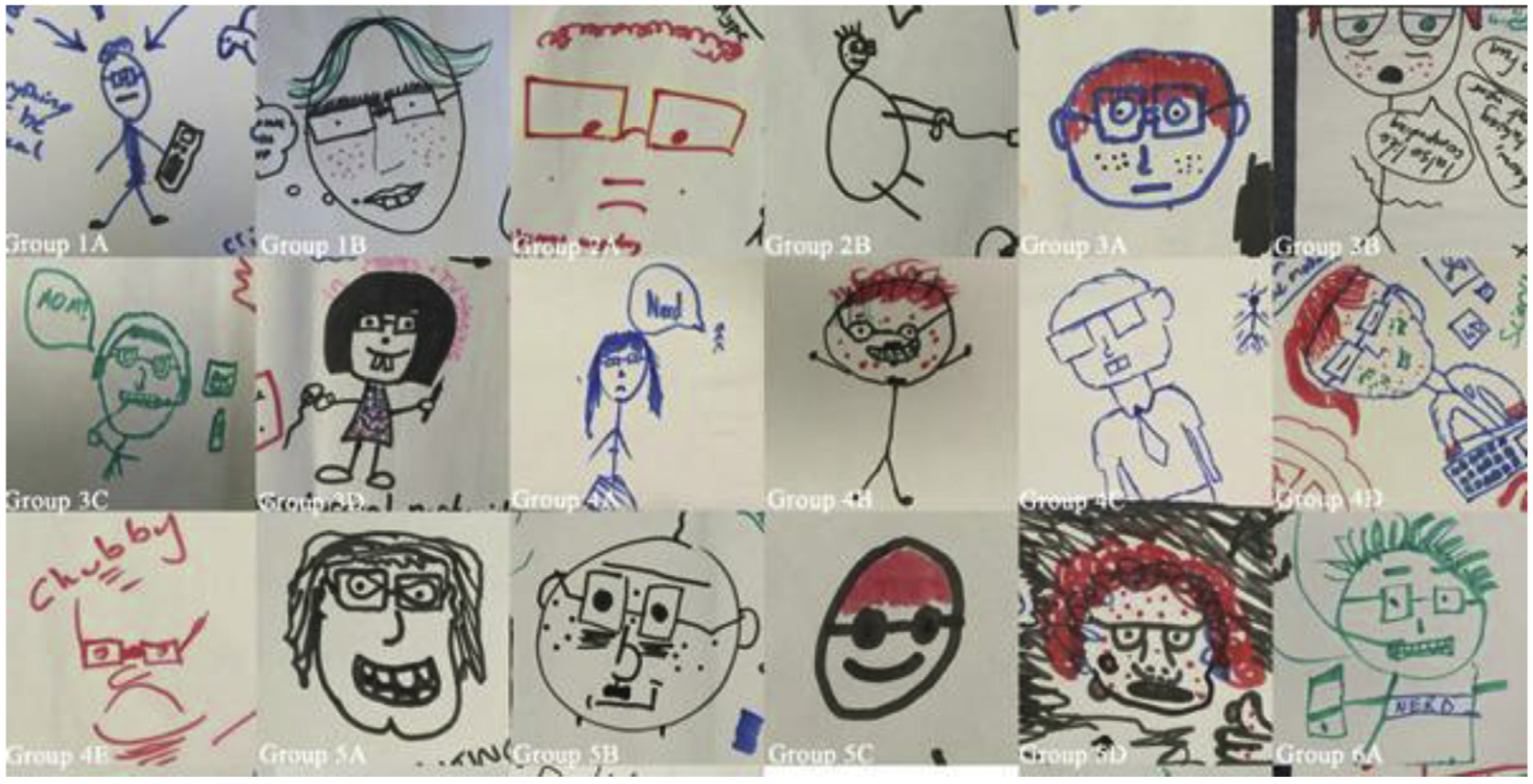

I’m not entirely certain about the origin of this “stereotype,” but it’s likely one of the most pervasive and long-standing misconceptions. A study by Heriot-Watt University revealed a telling insight: when students aged 13–17 were asked to draw their perception of Computer Science, many depicted scientists as boys, nerds, and geeks.

Caption: When students aged 13–17 were asked to draw their perception of Computer Science, many depicted scientists as men.

This narrative is fundamentally flawed. While it’s true that currently fewer women are represented in scientific fields, this does NOT imply that women are inherently incapable of scientific pursuits.

Numerous brilliant female scientists and researchers demonstrate the contrary. According to statistics, up to 30% are women, conclusively proving that women can not only engage in scientific research but excel in it. I can confidently affirm that women are conducting groundbreaking scientific work every single day. Especially for Vietnam, there are so many talented Vietnamese women are working in Computer Sciences, with a variety of domain (e.g., Computer Vision, Natual Language Processing, Machine Learning, etc.). Please see Vietnamese Women in Computer Science for reference.

Computer Scientist is a men… working in a dark, cool, eccentric room

Beyond gender-specific stereotypes, I’ve personally grappled with the unsettling notion that pursuing scientific research would disconnect me from a passionate, diverse community. Perhaps this stems from media representations (e.g., Sheldon Cooper in Big Bang Theory) that have perpetuated a narrow, sensationalized image of scientists as exclusively “cool” or “eccentric.”

During a course on Educational Psychology, I encountered a fascinating concept that articulated my unease: “ambient belonging”.

Consider the stereotypical image of a computer scientist: often visualized as someone sequestered in a dark room, programming with intense focus. Research has demonstrated that such preconceived notions of ambient belonging can significantly diminish students’ interest in pursuing scientific fields!

Caption: A short fun video about "What people think programming is, and what is actually is..."

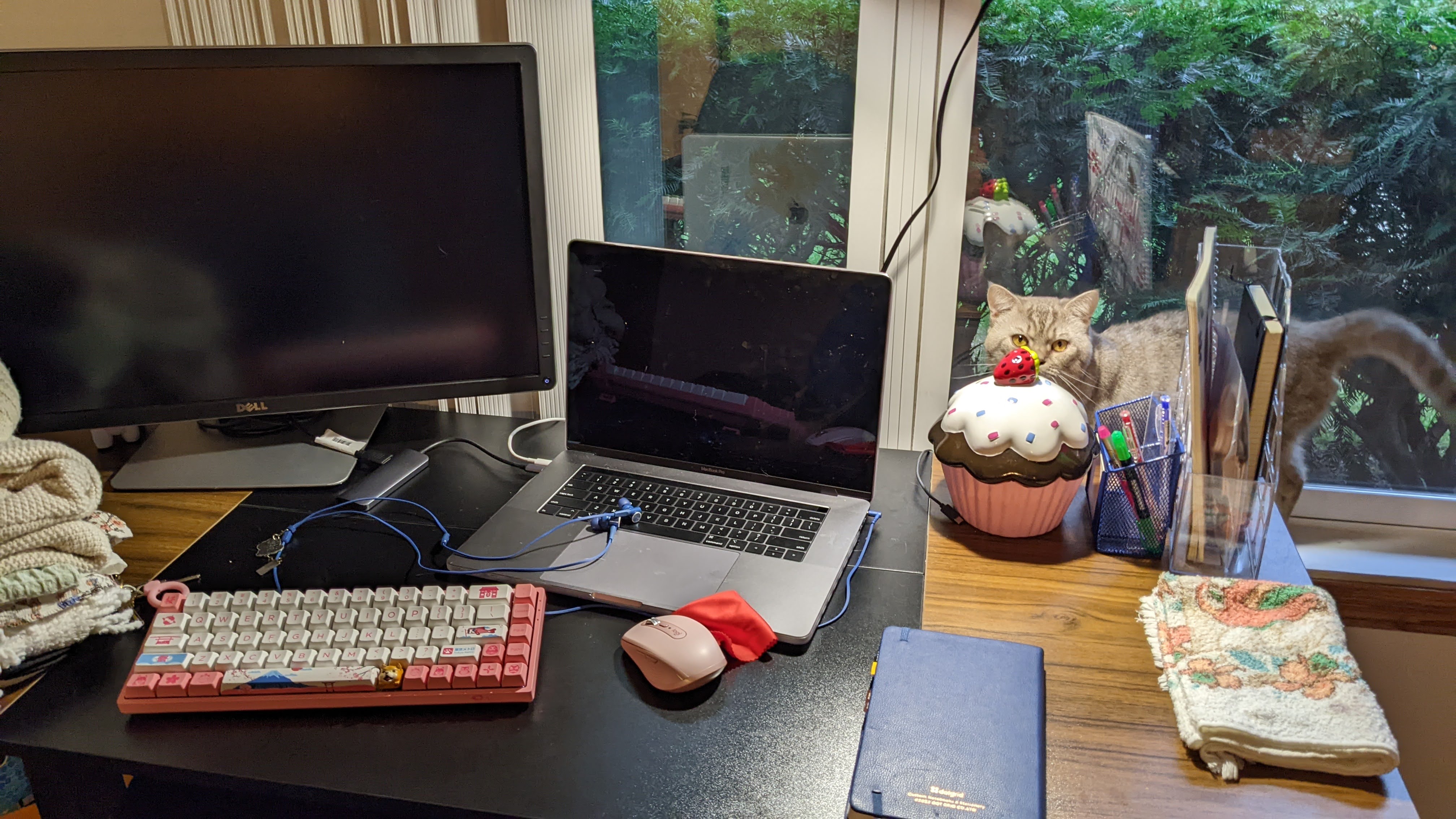

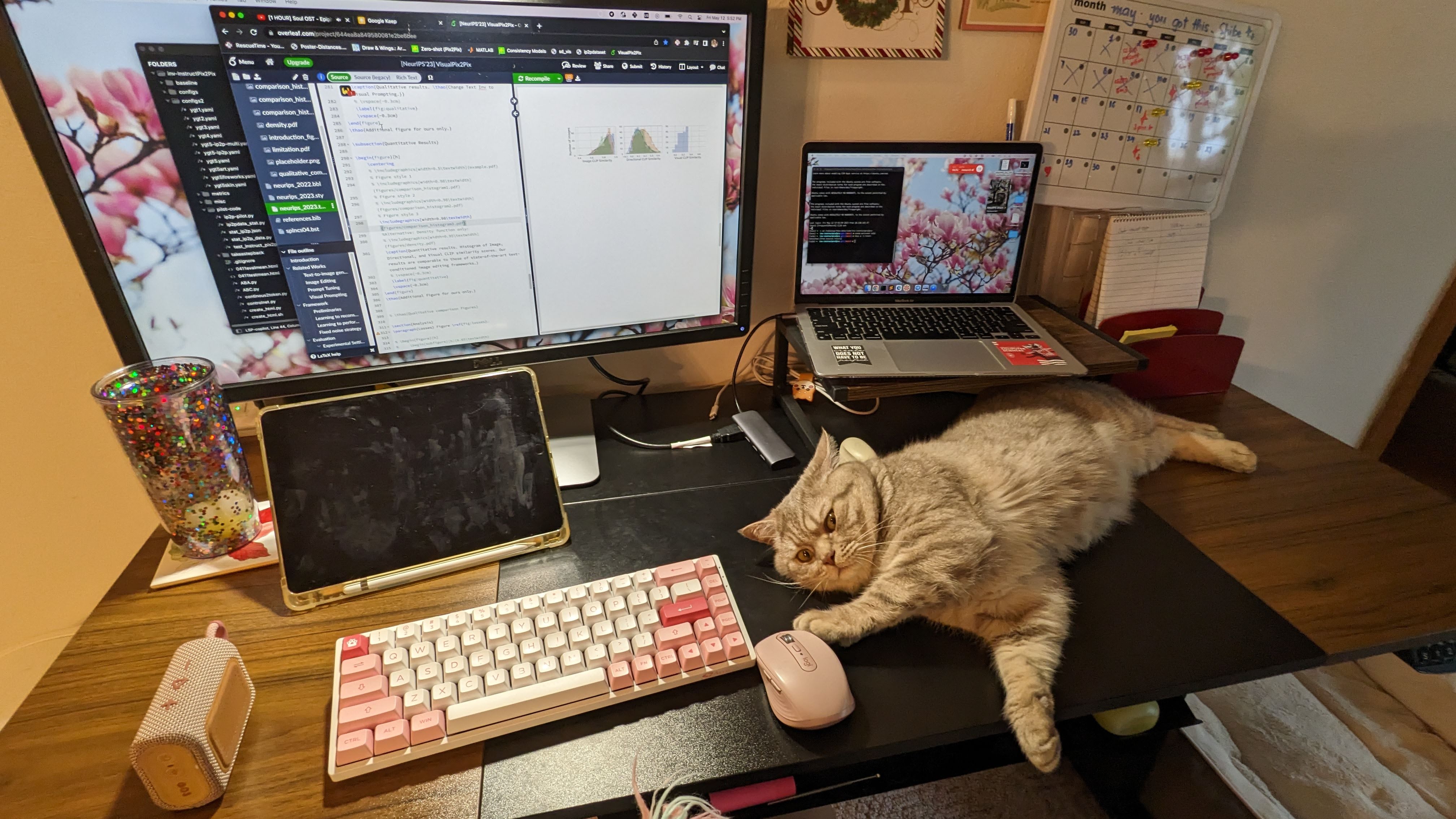

Candidly, I once subscribed to these stereotypes. However, I’ve since recognized their absurdity. The reality is far more nuanced: you can personalize your workspace however you desire, and not every programmer fits the narrow, dramatized television portrayal. My own workspace at VinAI—and those in large tech companies—are testament to this diversity. Most of the time, your working enviroments will be neutral and… even a bit “boring”! (But you and decorate in the way that you want~)

My desk at home (Can you spot the cat?) |

My desk at home (yes, with my cat as "decorative object") |

My first-year office at University of Wisconsin-Madison |

My desk at Adobe Reseach @ Summer 2024 |

Quick summary:

Women can do Computer Science, and the “stereotypes” you imagine about the field are likely far from reality.

The fundamental truth is simple: you can be authentically yourself and still pursue scientific excellence.

Computer Science is Reserved for Geniuses

It might be true many people with “geniuses talent” choose to pursue science and technology or scientific research. However, in reality, there are far more “ordinary” people in Computer Science than you might think.

A study has showed that using terms like “nerdy” and such negatively impacts women’s motivation to engage in STEM. This stereotype shouldn’t exist. I might not (still) have not “too-much” experience in the field, so I’ll quote Professor Matt Might words here:

What doesn't matter

There's a ruinous misconception that a Ph.D. must be smart.

This can't be true.

A smart person would know better than to get a Ph.D.

"Smart" qualities like brilliance and quick-thinking are irrelevant in Ph.D. school.

Students that have made it through so far on brilliance and quick-thinking alone wash out of Ph.D. programs with nagging predictability.

Let there be no doubt: brilliance and quick-thinking are valuable in other pursuits.

But, they are neither sufficient nor necessary in science.

Certainly, being smart helps. But, it won't get the job done.

Moreover, as anyone going through Ph.D. school can tell you: people of less than first-class intelligence make it across the finish line and leave, Ph.D. in hand.

As my advisor used to tell me, "Whenever I felt depressed in grad school--when I worried I wasn't going to finish my Ph.D.--I looked at the people dumber than me finishing theirs, and I would think to myself, if that idiot can get a Ph.D., dammit, so can I."

Since becoming a professor, I finding myself repeating a corollary of this observation, but I replace "getting a Ph.D." with "obtaining grant funding."

Women Studying Computer Science Are “Unattractive” or Will Stay Single?

I’ve heard this stereotype too often from friends and relatives. Even at Hanoi University of Science and Technology (HUST), there’s an infamous saying:

“HUST boys are like parrots,

HUST girls are like baked cassava roots.”

(In Vietnamese: “Trai Bách Khoa như chim Anh Vũ; Gái Bách Khoa như củ sắn lùi”)

This caustic comparison reveals more than just a crude joke—it exposes a pervasive social narrative that reduces women in technical fields to being unattractive, undesirable, or socially unsuccessful. The stereotype suggests that female students who pursue science and technology somehow sacrifice their femininity or romantic prospects.

Research supports that women often face a societal conflict between pursuing STEM and adhering to traditional gender roles. Studies suggest that romantic goals, tied to societal expectations, can discourage women from engaging in STEM. For example, research found that women exposed to romantic contexts reported less positive attitudes toward STEM, while men showed no such conflict.

Prof. Jelena Diakonikolas & Prof. Ilias Diakonikolas @ UW-Madison Faculty couples and how they balance personal & professional bliss |

Prof. Dhruv Batra & Prof. Devi Parikh @ Georgia Tech AMP alums Dhruv Batra and Devi Parikh get married |

| Some faculty couples in Computer Science that I know~ I bet there are many more! | |

From my personal experience, studying technology has been anything but a social limitation. If anything, it has been incredibly empowering. The skills I’ve developed—critical thinking, problem-solving, technical expertise—have made me more confident and interesting. Contrary to the stereotype, studying STEM has allowed me to meet incredibly talented and kind peers, including amazing male colleagues who value intelligence and passion.

Just look around, and you’ll see that scientists can love, live, and thrive just like anyone else. My journey in STEM has taught me that attractiveness is about so much more than appearance—it’s also about passion, intelligence, and the ability to do/ join impactful research!

To anyone who still believes that girls in STEM/ Computer Science are “unattractive” or unlikely to find love: think again!

Me at VinAI Research office @ 2020 |

With my undergrad classmates @ 2020 |

With my summer intern mentor(s) @ Summer 2024 |

Me with my labmates at CVPR @ 2024 |

I hope this article gives you a new perspective and (even better) inspires Vietnamese students who are unsure about their choice of major to confidently pick STEM, especially pursuing a graduate degree in Computer Science.

“Remember that life is a whole spectrum. And you will find your place!”

References:

- First Generated Image: bing.com/images/create

- Second Generated Image: bing.com/images/create

- Cheryan, S., Plaut, V. C., Davies, P. G., & Steele, C. M. (2009). Ambient belonging: How stereotypical cues impact gender participation in computer science. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 1045–1060. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19968418/

- Berg, T., Sharpe, A., & Aitkin, E. (2019). Females in computing: Understanding stereotypes through collaborative picturing. Computers in Human Behavior, 91, 72–83. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360131518301829

- Bian, L., Leslie, S.-J., & Cimpian, A. (2017). Evidence of bias against girls and women in contexts that emphasize intellectual ability. American Psychologist, 72(1), 1–16. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2018-62311-015

- Cheryan, S., Plaut, V. C., Handron, C., & Hudson, L. (2013). The stereotypical computer scientist: Gendered media representations as a barrier to inclusion for women. Sex Roles, 69(1), 58–71. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2013-22691-001

- Gaucher, D., Friesen, J., & Kay, A. C. (2011). Evidence that gendered wording in job advertisements exists and sustains gender inequality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(1), 109–128. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21381851/

- McPherson, E., Park, B., & Ito, T. A. (2018). The role of prototype matching in science pursuits: Perceptions of scientists that are inaccurate and diverge from self-perceptions predict reduced interest in science careers. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(6), 881–898. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217754069

- Park, L. E., Young, A. F., Troisi, J. D., & Pinkus, R. T. (2011). Effects of everyday romantic goal pursuit on women’s attitudes toward math and science. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(9), 1259–1273. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211408436

- Starr, C. R. (2018). “I’m not a science nerd!”: STEM stereotypes, identity, and motivation among undergraduate women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 42(4), 489–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684318793848